Natural Selection: A Primer

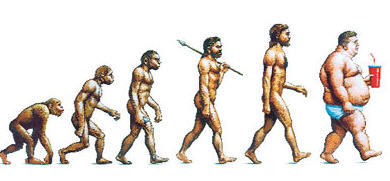

One hundred and thirty-nine years ago, the British naturalist Charles Darwin rattled the world with his theory of natural selection. According to his theory, human beings were not “placed” fully formed onto the earth. Instead, they were an evolved species, the biological descendants of a line that stretched back through apes and back to ancient simians. In fact, Darwin said, human beings shared a common heritage with all other species.

Since Darwin’s time, scientists have built on the theory of natural selection with modern discoveries, most notably in the area of genetics. Today modern Darwinians hypothesize that evolution occurs in the following manner: All living creatures are “designed” by specific combinations of genes. Genes that produce faulty design features, such as soft bones or weak hearts, are largely eliminated from the population in two ways. First, species with those characteristics simply don’t survive the elements long enough to reproduce and pass along their genes. This is called environmental selection. Second, these same creatures are unattractive to other members of their group because they appear weak and less likely to reproduce. They don’t mate and therefore don’t reproduce. This is called sexual selection.

The genes that survive environmental and sexual selection are passed on to succeeding generations. At the same time, genetic mutations occasionally crop up. They produce new variations—say, improved hearing or sharp teeth. The characteristics that help a species thrive and propagate will survive the process of natural selection and be passed on. Those that don’t are weeded out. By these means, species evolve with stable genetic profiles that optimally fit the environmental niches they occupy. Thus, fish that live at the bottom of the sea can see in the darkness, and dogs that prey on burrowing rodents have keen senses of smell. Species become extinct and new species emerge when radical shifts in environmental conditions render obsolete one set of design features and offer opportunities for a new set to prosper.

Darwin and his proponents over the decades have used the theory of natural selection to explain how and why human beings share biological and physical traits, such as the opposable thumb and keen eyesight, with other species. Evolutionary psychologists go further. They use the theory of natural selection to explain the workings of the human brain and the dynamics of the human group. If evolution shaped the human body, they say, it also shaped the human mind.

Evolutionary psychologists describe the “creation” of that mind in this way: The first two-legged hominids emerged after a prolonged period of global cooling approximately four million years ago. A range of variations in their biogenetic design briefly flourished and then became extinct, leaving Homo sapiens as the all-conquering survivor.

The success of Homo sapiens was no fluke. The greatly enlarged brain of the species made survival in the unpredictable environment of Africa’s vast Savannah Plain possible. Much of that brain’s programming was already in place, an inheritance from prehuman ancestors. But eventually, thanks to natural selection, other “circuits” developed, specifically those that helped human beings survive and reproduce as clan-living hunter-foragers.

For most of our history, this is how people lived, until their world radically changed with the invention of agriculture approximately 10,000 years ago. This suddenly allowed people to accumulate wealth and live in larger numbers and in greater concentrations, and freed many from hand-to-mouth subsistence. From this agricultural period, fast and short steps have brought us to modern civilization, with its enormous social changes wrought by advanced technology and communications.

But evolutionary psychologists assert there are three reasons that these changes have not stimulated further human evolution. First, as far back as 50,000 years ago, humans had become so scattered across the planet that beneficial new genetic mental mutations could not possibly spread. Second, there has been no consistent new environmental pressure on people that requires further evolution. In other words, no eruptions of volcanoes or glaciers plowing south have so changed the weather or the food supply that people’s brain circuitry has been forced to evolve. Third, 10,000 years is insufficient time for significant genetic modifications to become established across the population. Thus, evolutionary psychologists argue that although the world has changed, human beings have not.

Managerial Implications of Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychology offers a theory of how the human mind came to be constructed. And that mind, according to evolutionary psychologists, is hardwired in ways that govern most human behavior to this day. But not all inborn traits are relevant to people trying to manage companies—for instance, an evolutionary psychologist’s view on how people are “programmed” to raise children probably belongs in another article. Several key hypotheses among evolutionary psychologists speak directly to executives, however, because they shed light on how human beings think and feel and how they relate to one another. Let’s consider these topics in turn.

Thinking and Feeling.

Life on the Savannah Plain was short and very fragile. The food supply and other resources, such as clothing and shelter, were unreliable and varied in quality. Natural life-threatening hazards abounded. As weak, furless bipeds, human beings’ strength lay in their minds. The thoughts and emotions that best served them were programmed into their psyches and continue to drive many aspects of human behavior today. Chief among them are:

Emotions Before Reason. In an uncertain world, those who survived always had their emotional radar—call it instinct, if you will—turned on. And Stone Age people, at the mercy of wild predators or impending natural disasters, came to trust their instincts above all else. That reliance on instinct undoubtedly saved human lives, allowing those who possessed keen instincts to reproduce. So for human beings, no less than for any other animal, emotions are the first screen to all information received.

Today businesspeople are often trained to dispense with emotions in favor of rational analysis and urged to make choices using logical devices such as decision trees and spreadsheets. But evolutionary psychology suggests that emotions can never fully be suppressed. That is why, for instance, even the most sensible employees cannot seem to receive feedback in the constructive vein in which it is often given. Because of the primacy of emotions, people hear bad news first and loudest.

Emotions can never be fully suppressed—that is why giving feedback can be so difficult.

Managers should not assume they can balance positive and negative messages. The negatives have by far the greater power and can wipe out in one stroke all the built-up credit of positive messages. In fact, because of the primacy of emotions, perhaps the most discouraging and potentially dangerous thing you can do is to tell someone he or she failed. Be careful, then, of who you put in charge of appraisal systems in your organization. These managers must be sensitive to the emotional minefields that all negative messages must navigate.

Loss Aversion Except When Threatened. Human beings who survived the harsh elements of the Stone Age undoubtedly tried to avoid loss. After all, when you are living on the edge, to lose even a little would mean that your very existence was in jeopardy. Thus, it follows that ancient hunter-gatherers who had just enough food and shelter to survive weren’t big risk takers. That doesn’t mean they never explored or acted curious about their world. Indeed, when the circumstances felt safe enough, that is very likely just what they did. We can see this same kind of behavior in children; when they are securely attached—confident that an adult will prevent any harm from coming to them—they can be quite adventurous. But when harm looms, such behavior evaporates. In the Stone Age, this cautious approach to loss certainly increased human beings’ chances of staying alive—and thus reproducing. Their descendants, with this genetic inheritance, would therefore also be more likely to avoid loss.

Let’s take aversion to loss one step further, beyond living close to the margin. Sometimes our ancestors lived below the margin, with barely enough food to get by and no secure shelter. Or they experienced a direct threat to their lives from a predator, a natural disaster, or another human being. There are no historical records of what Stone Age people did in such circumstances, but it stands to reason that they fought furiously. And certainly those human beings willing to do anything to save themselves would be those that lived to pass on the genes that encoded such determination.

Thus, we are hardwired to avoid loss when comfortable but to scramble madly when threatened. Such behavior can be seen in business all the time. Every financial-markets trader can recite the old saw, “Cut your losses and let your profits run.” The same traders will also tell you that this rational rule of thumb is the hardest thing they have to learn on the job. Their instinct is to take risks as soon as losses start to mount. A stock starts to fall and they double up their positions, for instance. That’s the frantic fight to survive in action. And similarly, it’s instinct that drives people to sell while a stock is still rising. That’s risk aversion in action. That said, experienced traders know how damaging these instincts are; and rules and procedures that force them to cut their and let their lossess and let their profits run. But without such rules and procedures, human nature would most likely take its course.

Consider what happens when a company announces impending layoffs but does not specify which people will lose their jobs. In these situations, people will do almost anything to save their jobs and avoid the pain of such loss. How else can you expain the kinds of leaps in productivity we see after a company makes usch an announcement? By another dynamic emerges when a company announces that entire divisions will close. The people affected—those who cannot escape the loss—do the unthinkable. They scream at their bosses or perform other acts of aggression. Instead of acting rationally, they flame out in a panic to survive. On the Savannah Plain, these desperate efforts apparently paid off. But a flaming out when feeling desperate is hardly a blueprint for survival in the modern organization.

Besides being aware that people are hardwired to act desperately when directly threatened, managers must heed another message. You can ask people to think outside the box and engage in entrepreneurial endeavors all you want, but don’t expect too much. Both are risky behaviors. Indeed, any kind of change is risky when you are comfortable with the status quo. And evolutionary psychologists are not surprised at all by the fact that, despite the excellent press that change is given, almost everyone resists it—except when they are dissatisfied.

But what of those Silicon Valley entrepreneurs who have made a high art form of bet-the-company behaviors? Evolutionary psychology would tell us that these individuals are the type of men and women who over the millennia have sought thrills and lived to tell about them. After all, evolutionary psychology doesn’t discount individual personality differences. Human behavior exists along a continuum. On average, people avoid risk except when threatened. But imagine a bell curve. At one end, a small minority of people avidly seek risk. end, a small minority of so cautious they won’t risks even when their depend on it. The vast majority fall in between, avoiding loss when comfortable with life and fighting furiously when survival requires them to do so.

Managers would do well to assume that the people with whom they work fall under the bell of the continuum. Perhaps the most concrete take-away from this contention is that if want people to be risk takers, frame the situation as threatening. The competition is goinig to destroy us with a new product. Or, our brand has lost its cache and market share is slipping fast. On the other hand, if you want people to eschew risk-taking behaviors, make sure they feel secure by telling them how successful the business is.

That advice does raise a question, however. What if you want people in your organization to be creative, to explore new ideas, and to experiment with different approaches to business? After all, most executives want their people to be neither outlandish fantasists nor mindless robots. The happy medium is somewhere between the extremes. What is a manager to do? If you invite people to make mistakes in the name of creativity, they won’t. They will see this as empty rhetoric; in fact, instinct will tell them that making mistakes involves loss (possibly of their jobs). But if you come clean and tell them that mistakes will be penalized, again, you’ll get nothing. Sadly, evolutionary psychology brings this managerial quandary to the surface but cannot solve it. Effective managers need to be adept at the very difficult task of framing challenges in a way that neither threatens nor tranquilizes employees.

Confidence Before Realism.

In the unpredictable and often terrifying conditions of the Stone Age, those who survived surely were those who believed they would survive. Their confidence strengthened and emboldened them, attracted allies, and brought them resources. In addition, people who appeared self-confident were more attractive as mates—they looked as if they were hardy enough to survive and prosper. Thus, people who radiated confidence were those who ended up with the best chances of passing on their genes. The legacy of this dynamic is that human beings put confidence before realism and work hard to shield themselves from any evidence that would undermine their mind games.

Countless management books have been written extolling the virtues of confidence; they cleverly feed right into human nature. Given their biogenetic destiny, people are driven to feel good about themselves. But if you operate on a high-octane confidence elixir, you run into several dangers. You neglect, for instance, to see important clues about impending disasters. You may forge into hopeless business situations, assuming you have the right stuff to fix them. The propensity to put confidence before realism also explains why many businesspeople act as though there isn’t a problem they can’t control: The situation isn’t that bad—all it needs is someone with the right attitude.

The truth is, even with self-confidence we cannot control the world. Some events are random. Ask any CEO who has been blamed for a company’s poor performance wrought by an unpredictable lurch in exchange rates. Or ask any young M.B.A. sent in by corporate headquarters to turn around a factory bleeding red. He might go in with high hopes, but a year or two later he’ll be talking about all the factors outside his control that he couldn’t conquer.

What’s the message for managers? Perhaps that it makes sense sometimes to challenge human nature and ask questions such as, Am I being overly optimistic? or Am I demanding too much of a certain manager? Such questions force us to separate confidence from reality, for as evolutionary psychology tells us, our minds won’t instinctively do that.

Classification Before Calculus.

The world of hunter-gatherers was complex and constantly presented new predicaments for humans. Which berries can be eaten without risk of death? Where is good hunting to be found? What kind of body language indicates that a person cannot be trusted?

In order to make sense of a complicated universe, human beings developed prodigious capabilities for sorting and classifying information. In fact, researchers have found that some nonliterate tribes still in existence today have complete taxonomic knowledge of their environment in terms of animal habits and plant life. They have systematized their vast and complex world.

In the Stone Age, such capabilities were not limited to the natural environment. To prosper in the clan, human beings had to become expert at making judicious alliances. They had to know whom to share food with, for instance—someone who would return the favor when the time came. They had to know what untrustworthy individuals generally looked like, too, because it would be foolish to deal with them. Thus, human beings became hardwired to stereotype people based on very small pieces of evidence, mainly their looks and a few readily apparent behaviors.

Whether it was sorting berries or people, both worked to the same end. Classification made life simpler and saved time and energy. Every time you had food to share, you didn’t have to figure out anew who could and couldn’t be trusted. Your classification system told you instantly. Every time a new group came into view, you could pick out the high-status members not to alienate. And the faster you made decisions like these, the more likely you were to survive. Sitting around doing calculus—that is, analyzing options and next steps—was not a recipe for a long and fertile life.

And so classification before calculus remains with us today. People naturally sort others into in-groups and out-groups—just by their looks and actions. We subconsciously (and sometimes consciously) label other people—“She’s a snob” or “He’s a flirt.” Managers are not exempt. In fact, research has shown that managers sort their employees into winners and losers as early as three weeks after starting to work with them.